UNPLUG AND PLAY

Registered Play Therapist Hannah Hollett on why child’s play is more important than ever

On January 1, 2007, the American Academy of Pediatrics published an article about the importance of free play and how crucial it is for a child’s development. Dr. Ken Ginsburg, a professor of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, sited nine factors that were changing the dynamic of family routines—things like two working parents and a hurried lifestyle. He didn’t list TV and video games until number 8.

Eight days later, Apple CEO Steve Jobs rolled out the iPhone.

It’s been 17 years since the iExplosion. Today, the prevalence of parents with iPhones is followed closely by children with iPads. In a 2023 U.S. Census report, 80% of households with children owned tablets.

Experts often weigh in on how and why families should limit their screen time. But it can be a difficult argument to make to overworked parents. Kids on screens are quiet, the house remains tidy, and parents have uninterrupted time to get things done.

But what do children stand to gain when they ditch the screens and play with toys?

Registered play therapist and licensed social worker Hannah Hollett of Grace Therapy in Charlotte built her career on the importance of play. “(Free) play helps kids with coordination, fine motor skills, gross motor skills, and just being able to move their bodies,” she says. That’s true whether it’s babies just beginning to learn independent play, toddlers who parallel play (play alongside each other), or preschool and elementary-aged children learning to play cooperatively.

Active play helps them develop mentally, too. “It helps children problem solve, it helps them become better at memory skills, better at creative thinking,” Hollett says. “They can express themselves more effectively and process what’s going on in their minds when they don’t have the words for it.”

Screens limit children’s imagination by providing the visuals, scenarios, and very often the choices. Playing with toys allows children more of a clean slate.

“Boredom is good for kids,” Hollett says. “When they’re on screen time for too long, that puts a hold on being creative, problem-solving, moving their bodies, and all the different things play does. They get their dopamine too quickly.”

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter and hormone that helps provide feelings of pleasure, satisfaction, and motivation. Excess screen time prevents children from learning different ways to find that dopamine boost on their own and can stunt their brain development.

While electronic devices create a virtual reality, they limit interactions with other children and circumstances they might encounter in the world. “The device is an escape,” Hollett says. “You can learn things from it. However, there’s nothing that creates that feeling of being outside or being with friends or really having to problem solve or cope with uncomfortable feelings. When we have the screen time, you won’t feel those feelings. But in reality, that’s not how it works.”

Screens are isolating. Toys open the door to interactive play with siblings, friends, parents, and caregivers. Hollett first witnessed the power of play while working in foster care. She was working with a 10-year-old boy, who’d been physically and sexually abused and neglected. It was one of the worst cases her department had ever seen; his issues ranged from anxiety to cutting.

“I introduced play, and it lit up his world,” Hollett says. “He was able to process it and even talk about it while playing, and in ways that I didn’t think that he would ever be able to really speak about.”

After seeing his transformation, she decided to change her career trajectory from working with adults to focus on play therapy with children. “I saw how much of a benefit it was and how much quicker the kids would get better,” she says. She can’t point to one specific toy that made the difference with this 10-year-old boy; it was their interaction while playing with Legos, building blocks, and board games.

Hollett’s office is set up like a playroom, and she always lets the child choose the toy or game he or she wants to play. Often, it’s something as basic as darts or a board game that allows kids’ brains to relax and process feelings more effectively.

Hollett recommends a lesser-known game called Mancala. It’s a two-player wooden board game for children ages 8 and up and it’s believed to date back to ancient Egypt. The name comes from the Arabic word naqala, which means “to move,” referring to the glass beads you move around the board.

Hollett also loves arts and crafts that promote sensory play. “Sand toys, Play-Doh, slime, anything that is soft or has different textures,” she says. “Or fidgets. Mind puzzles like Kanoodle is a good one. Dolls, dollhouses, dinosaurs, army figures, stuffies.”

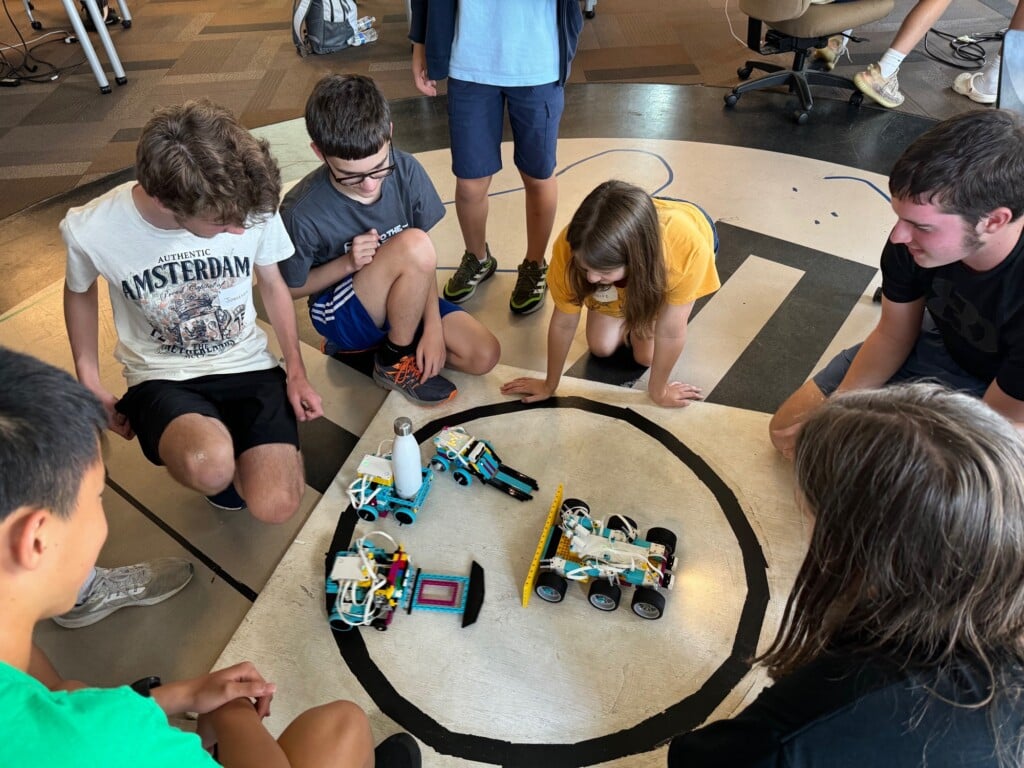

There’s a reason classic toys like Legos, Lincoln logs, and Tinker Toys have stood the test of time. “You can be super creative with them,” she says. “Create your own world, whatever world feels safe and happy to you.”

When it comes to Legos, which are often sold is sets with specific step-by-step directions now, she recommends letting children follow along if they choose, then taking the sets apart and keeping the pieces in a bin with other Legos. “Building the sets is great for the mind, it’s great for cognitive processing, but it doesn’t allow for creativity to happen,” she says. “Being able to be good problem solvers, that creates independence, too.”

CARROLL WALTON was a longtime sportswriter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution and co-authored Ballplayer, the Chipper Jones biography, in 2017. Today she lives in Charlotte with her husband and three sons and continues to freelance for several media outlets.